En Bloc: The Ins and Outs of the Collective Sale Fever

“En bloc” sales, or interchangeably referred to as collective sales, is a process whereby owners in a development band together to sell their properties jointly as an entity to a single buyer or a consortium with the intention of redeveloping the site into a new development. It is viable when there is development potential, where the land value is greater than the individual units’ aggregate value, or where the land is not optimally utilised.

More than 10 years following the first hype of collective sale in Singapore since 1994, we see stricter en bloc laws, tighter mortgage restrictions and even different planning legislations within the Singapore real estate scene. The phenomena of such a frenzied pace in enbloc sales throughout different periods of time has also been frequently described as a “rollercoaster ride”, where different key players in the scene hope for windfall gains and developers to secure the next plot of profitable land for their portfolio.

More than 10 years following the first hype of collective sale in Singapore since 1994, we see stricter en bloc laws, tighter mortgage restrictions and even different planning legislations within the Singapore real estate scene. The phenomena of such a frenzied pace in enbloc sales throughout different periods of time has also been frequently described as a “rollercoaster ride”, where different key players in the scene hope for windfall gains and developers to secure the next plot of profitable land for their portfolio.

Collective Sale Phenomenon: The Trigger

Collective Sale Phenomenon: The Trigger

Driven by the need to accommodate the increase in population in land scarce Singapore, the local planning agency, Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA), assigned higher development intensity or plot ratios for various sites in 1994. This has caused sites to become highly prized assets and triggered the collective sale phenomenon, where developers scramble to vie for the potentially profitable plots of land in Singapore.

Market Conditions and En Bloc Sales: How are they related?

It has generally been shown that collective sale activities have closely followed real estate market trends.[1] Whether a collective sale can be successful or not is therefore very much dependent on the prevailing state of the economy.

Boom periods are generally observed to experience a similar increase in en bloc transactions. This was especially so in the period of 1994-1997 where the collective sales phenomenon caused the private property market to peak in terms of number and the value of transactions. In 1997 alone, there was $1.12 billion worth of property sold collectively. Investor’s confidence peaked and the developers seized the chance to purchase available redevelopment sites to build up their land banks.

Other external economic factors have also been observed to have a correlation with en bloc statistics. These include the developmental tax rates and the current cyclical conditions of the economy.

Tug of War: GLS and Enbloc sales

Tug of War: GLS and Enbloc sales

Government Land Sales (GLS) has a direct impact on collective sale activities, depending on the amount of land released and the demand and supply conditions in the particular point in time. An oversupply of land is likely to result in a lower incentive for property owners to sell their units. Developers may also start to pace their supply.

This can be observed in 2017, where a lack of sites under the government land sales (GLS) programme, coupled with developers’ acute need to replenish land inventory and a recovering residential property market, were the main driving forces behind the en bloc sales boom in 2017. Between 2010 and 2013, the GLS supply from the Confirmed list averaged at about 9,000 units per annum. Oversupply concerns led to GLS supply being reduced to about 4,000[2] units per annum on average under the Confirmed List, between 2014 and 2017, which was also the same time period where en bloc sales were gaining momentum and growing towards its peak.

Legislative Milestones:

Legislative Milestones:

(i) 1999 Land Titles (Strata) Act

The passing of The Land Titles (Amendment) Act in 1999 scrapped the requirement of an unanimous vote in order to proceed with the sale. A majority vote is now sufficient to carry the deal through, as defined as:

- If the development is less than 10 years, not less than 90 percent of the owners according to share values will have to agree to the en bloc sale.

- If the estate is more than 10 years old, an 80 percent majority will be sufficient.

(ii) 2007: More stringent procedural rules

- No additional requirement for majority consent.

- New rules on formation and proceedings of the collective sale committee.

- STB is now empowered to increase sale proceeds for certain minority objectors and to disregard any technical or procedural irregularity that will not prejudice any SP’s interest and to make an order to amend the non-compliance.

- A cooling off period where the signatory is allowed to rescind his agreement.

- Requirement of an independent valuation report reflecting the value of the development as at the date of the close of the public auction or tender.

- Procedural changes to enhance transparency and certainty of the collective sale process.

The Key Players: (i) STB, (ii) Sellers and (iii) Developers

(i) Strata Titles Board (STB)

Collective sale applications by a subsidiary proprietor are subject to approvals from the Strata Titles Board (STB). Objectors and affected parties will attend a mediation session at the STB should they fail to reach an agreement and fix up a hearing date. The registrar of STB will inform all parties of the proposed panel who will hear the application and will ask if there is any objection to any panel member.

Responsibilities of STB:

- To ensure that the requisite majority has been obtained

- To ensure that the prescribed procedures have been complied with

- The proposed sale is bona fide and at arm’s length.

(ii) Sellers

The Subsidiary Proprietor:

A subsidiary proprietor (SP) is a purchaser to whom the developer has transferred ownership of a unit, as shown on the strata certificate of title.

The different profiles of key sellers[3] in the collective sale scene can be identified as –

1. Speculators

Speculators aim to quickly sell off the properties for higher prices and are not interested in holding onto the property for investments.

2. Specu-vestors

Similar to speculators, this group of people are however different in the sense that they are much more willing to hold onto their properties even if their investments may seem to be heading south.

3. Investors

Investors aim to enjoy rental income from their properties. They may be willing to sell it to enjoy capital gains.

4. Investor-occupiers

These are often new investors who want to enjoy the property returns during a boom market. They are also, however, willing to move into the property should they be unable to find suitable tenants.

5. Owner-Occupiers

Owner-occupiers are much less concerned about the financial gain they can stand to reap from a collective sale. Instead, they focus more on the non-tangible aspects of the property: its amenities, living environment and networks.

6. Foreign buyers

Foreign buyers are either those who have existing networks or family members within Singapore, and the other group which focus on the financial returns of the property as a form of investment.

7. Property agents

Agents are in the business of buying and selling. They are mainly driven by financial concerns.

(iii) Developers

A Brief Overview of the Collective Sale Process[4]

1. Preparation Stage – site identification

An intention to have a collective sale may first be initiated by the owners of a development, the developers, or even property consultants.

A preliminary study of the site will usually be conducted by the property consultants who are more familiar with such practices. Planning guidelines and developmental baselines of the site are some of the areas that the consultants will examine to determine if a collective sale is feasible.

A collective sale will be deemed viable only if the difference shows a potential for better utilisation of the existing site.

2. Feasibility study

Financial evaluations will be carried out to determine the monetary benefits accruing to the owners, as well as how lucrative a collective sale will be.

At this stage, it is necessary to first determine the value of the land (usually through residual method or comparison method of valuation) to find out how viable the site is for a collective sale.

3. Pre-launch stage

Surveys undertaken to establish the owner’s interest in the collective sale. A meeting will be held with all the owners with an explanation on what a CS exactly is with details on the apportionment of the sales proceeds.

Property consultants will address concerns and questions about the CS here. This stage is known to be tedious and may even be protracted since the consultants are required to approach the individual owners to convince them to go ahead with the collective sale.

4. Tender launch

Press releases informing all interested parties about the collective sale of the site is done by the marketing agent or developers of the site. Marketing of the site may be done either through a tender or private treaty. In the case of a collective sale, it is far more common for the process to be carried out through a tender.

A 10% deposit price is required once the bid is accepted.

5. Post-Tender – evaluation and negotiations

Bids received are valid for a month once the tender is closed. During this period, negotiations between the property consultants and the tenderers is possible if the reserve price is still not met.

Should the negotiations fall through, the sellers can still look for other interested parties to offer a better bid. However, once the one-month period ends, the sellers may have to resort to other methods of sale.

6. Completion stage

Once the Sale and Purchase (S&P) agreement is signed, the successful tenderer completes the sale within 3 months. During this period, the proceeds will be payable to the individual property owners, depending on the agreed apportionment.

7. Vacant possession

Upon the completion of the sale, the owners are then required to deliver vacant possession, usually within a period of 6 months. Owners here would have the time to look for other premises to relocate to or to invest in.

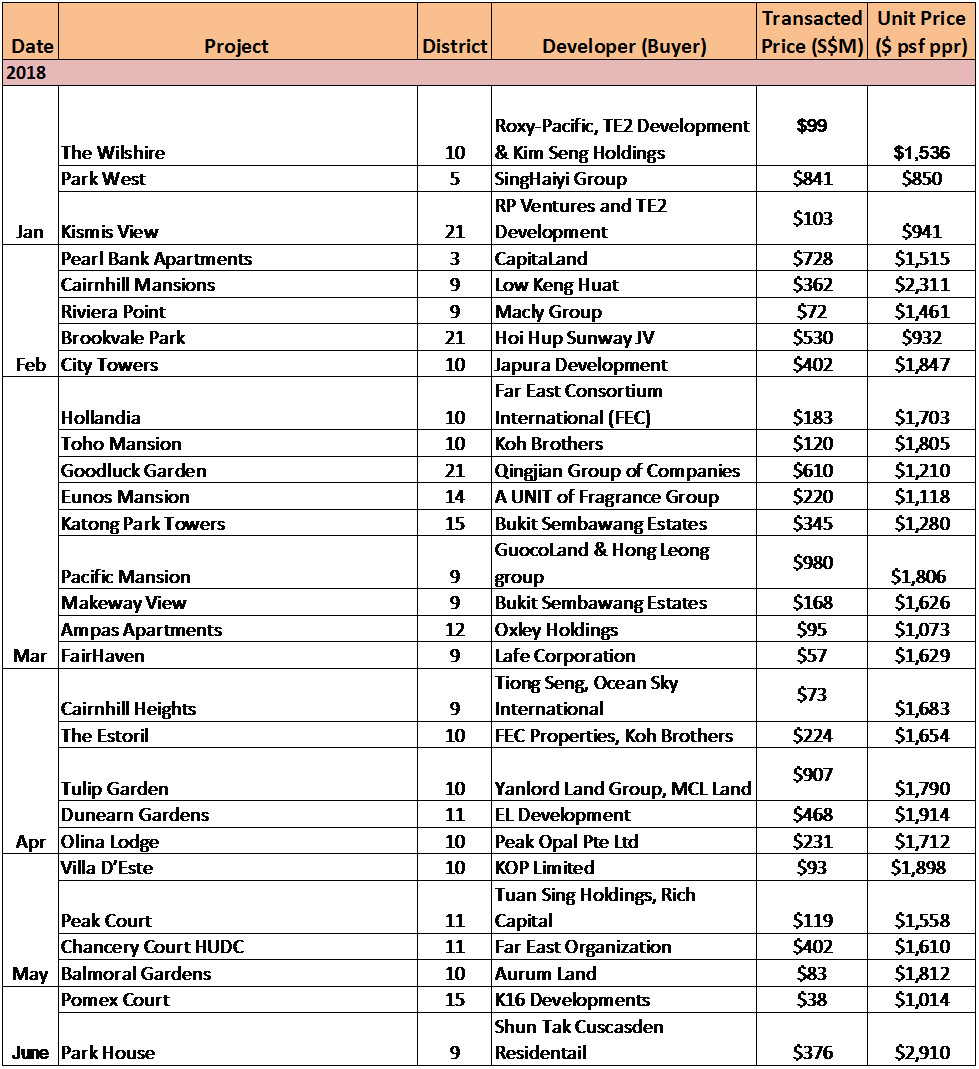

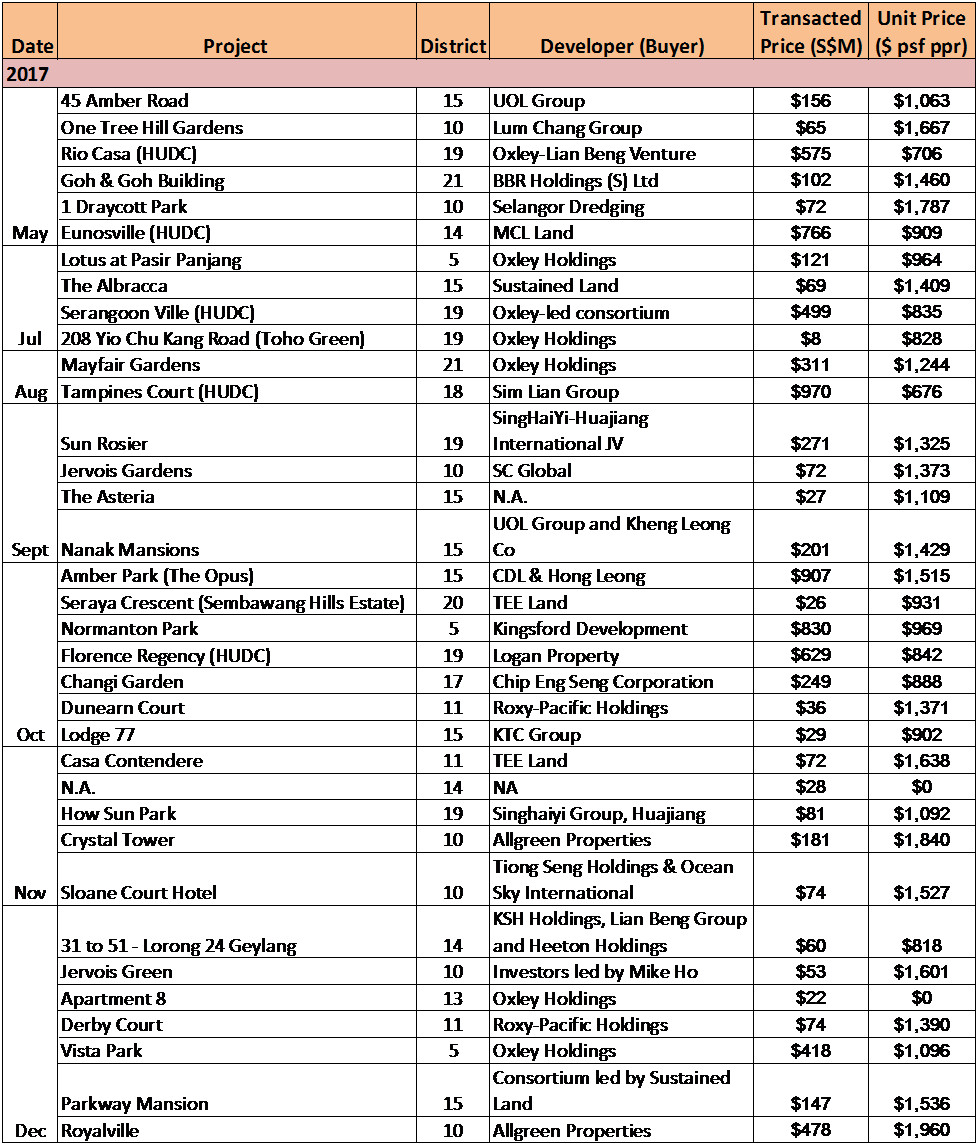

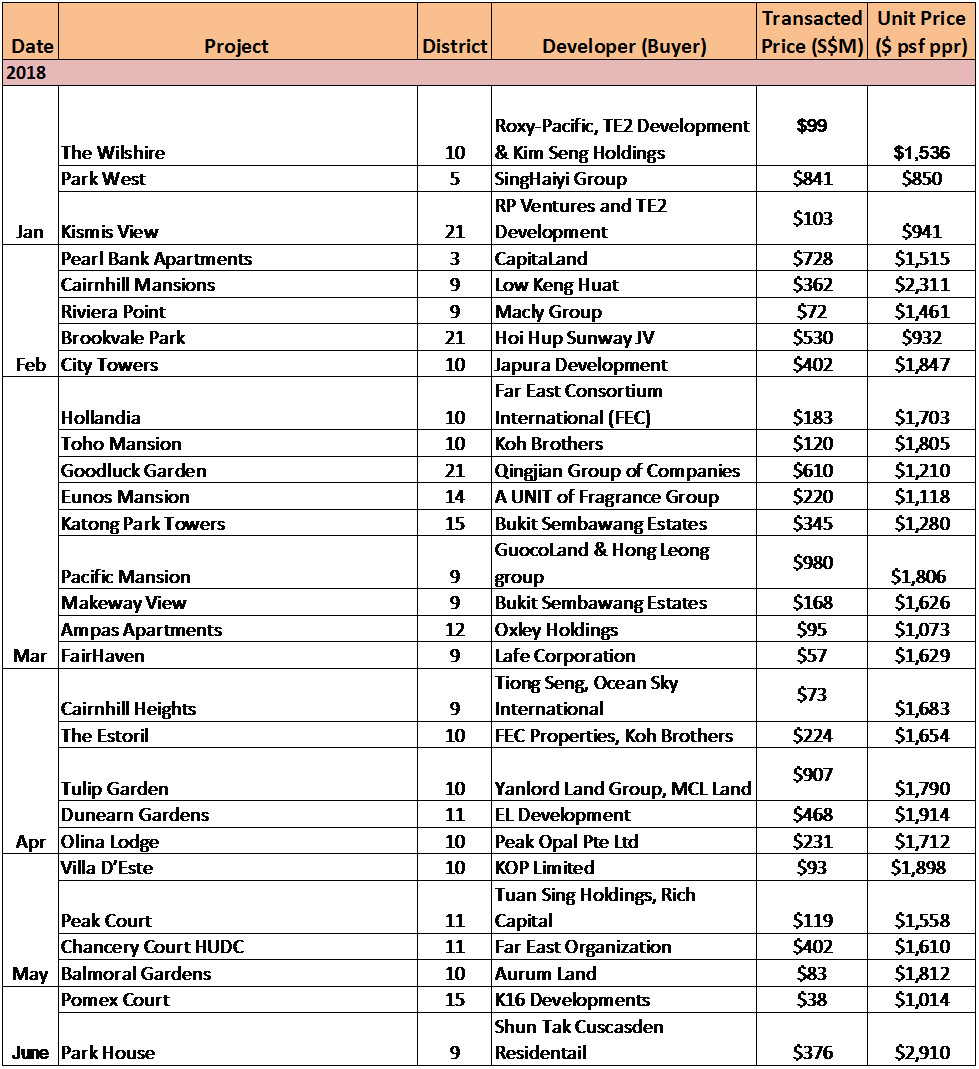

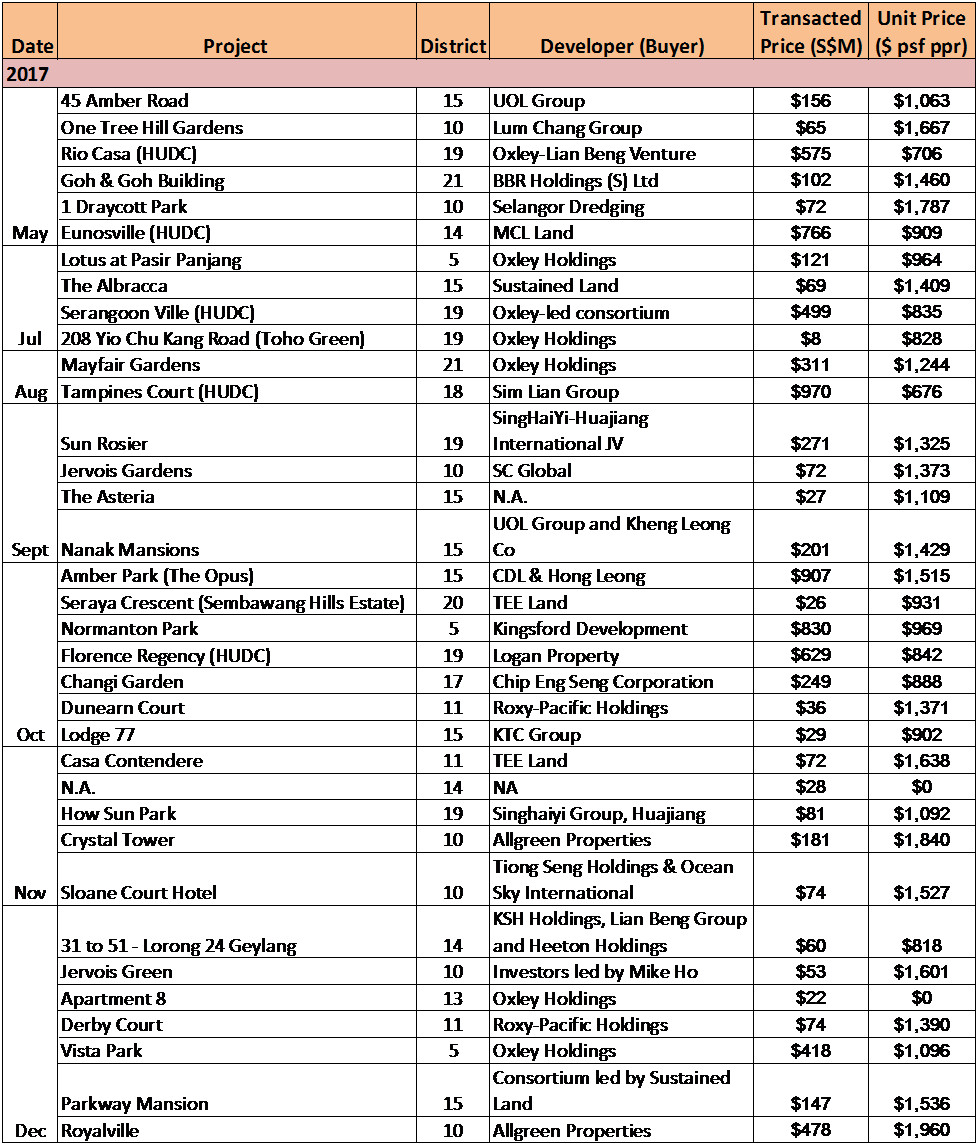

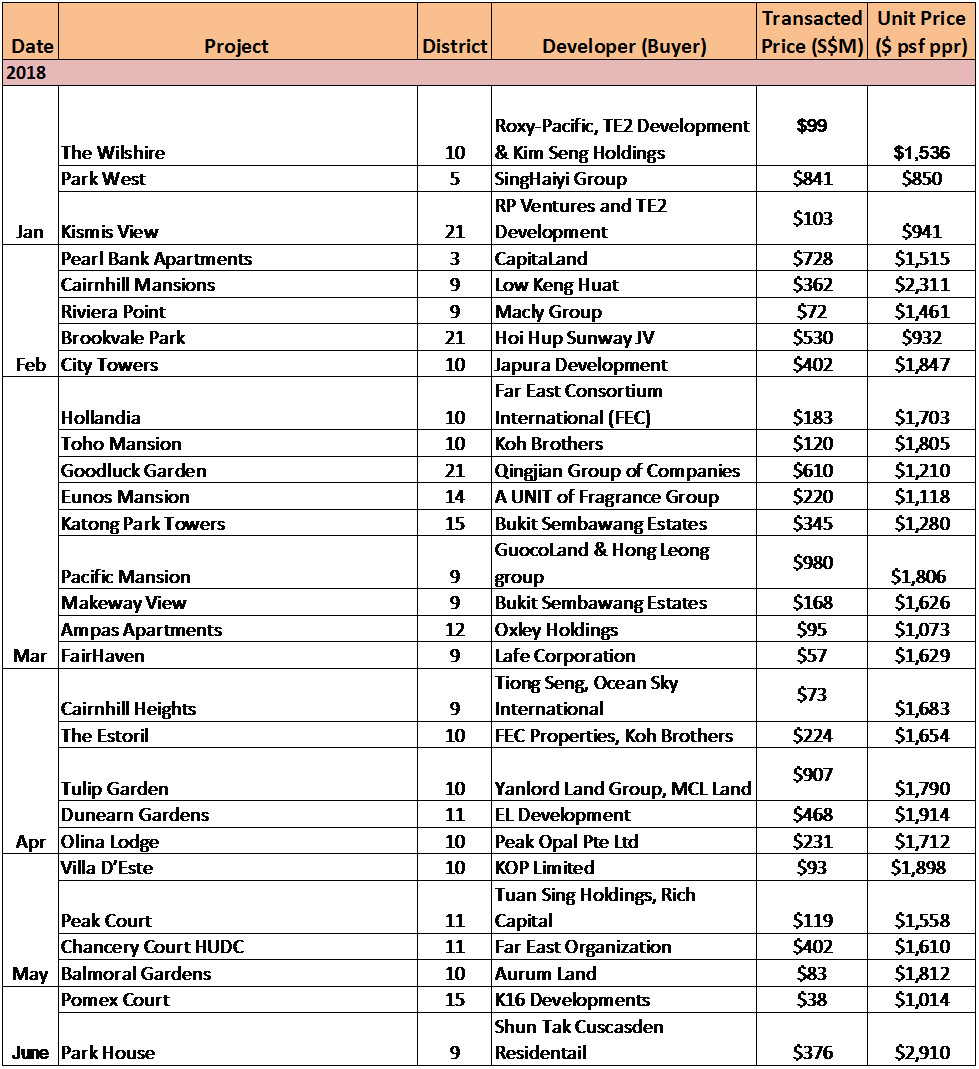

At a glance: Collective Sales from 2017-18 (Accurate as of 14 June 2018)

Compiled by Global Alliance Property, correct as of 14 June 2018.

The number of collective sale transactions recorded across 2017 to June 2018 remains as one of the all-time highest with the exception of the previous ‘en bloc fever’ in 2017. We expect that the number of transactions to continually increase in 2018, considering the current bullish market sentiments. The positive economic outlook is likely to translate to more, higher-value collective sale deals for the hopeful homeowners and land-hungry developers.

The sidelined minority

Owners are generally made up of a diverse lot as outlined above – be it as an owner-occupier or a property investor. It comes as no surprise that each group of owners are driven by different considerations for their own interest when considering whether to proceed with the collective sale or not.

The feverish pace of collective sales for strata developments have seen instances where unit owners were focused on achieving a collective sale of their developments for windfall gain. Minority of unit owners were seen to be sidelined in the sale process, mainly to be owners from the owner-occupier group who were less concerned with financial gains and more with their living environment. This results in bitter acrimony and strained relationships between owners who want to sell and those who do not want to sell their units.

In fact, underhand tactics and even taunting by unit owners were reported throughout the years in newspaper reports. Unit owners who refused to go en bloc were subjected to threats and even in some cases, vandalism.

The Caveat

While collective sales may indeed seem to look like big money or windfall fortune, the reality is that marketing a site alone can take long periods of time, and a sale may not even be guaranteed – this suggests that we need a strike a careful balance between what are the risks and rewards we can expect through a collective sale.

Future Outlook of CS scene in Singapore

Singapore’s real estate scene has been observed to be picking up, with a much slower rate of decline at 12% as compared to 2007’s 25% due to extensive cooling measures.

In fact, investments in GLS residential sites in H1 2018 is estimated at S$4-4.4 billion and is expected to be moderate for the full year as the H2 2018 GLS programme is unlikely to be aggressive. It is expected that en bloc sale sites will continue to be a major source of residential land supply for developers in 2018.

[1] Christudason, A. (2005). Impediments to the success of collective sales: Lessons for the property consultant.

[2] https://www.businesstimes.com.sg/hub-projects/property-2018-march-issue/mismatch-in-price-expectations-breaks-sales

[3] Christudason, A. (2010). Legal framework for collective sale of real estate in singapore: Pot of gold for investors? Journal of Property Investment & Finance, 28(2), 109-122. doi:10.1108/14635781011024854

[4] Christudason, A. (2005). Impediments to the success of collective sales: Lessons for the property consultant.

More than 10 years following the first hype of collective sale in Singapore since 1994, we see stricter en bloc laws, tighter mortgage restrictions and even different planning legislations within the Singapore real estate scene. The phenomena of such a frenzied pace in enbloc sales throughout different periods of time has also been frequently described as a “rollercoaster ride”, where different key players in the scene hope for windfall gains and developers to secure the next plot of profitable land for their portfolio.

More than 10 years following the first hype of collective sale in Singapore since 1994, we see stricter en bloc laws, tighter mortgage restrictions and even different planning legislations within the Singapore real estate scene. The phenomena of such a frenzied pace in enbloc sales throughout different periods of time has also been frequently described as a “rollercoaster ride”, where different key players in the scene hope for windfall gains and developers to secure the next plot of profitable land for their portfolio. Collective Sale Phenomenon: The Trigger

Collective Sale Phenomenon: The Trigger Tug of War: GLS and Enbloc sales

Tug of War: GLS and Enbloc sales Legislative Milestones:

Legislative Milestones: